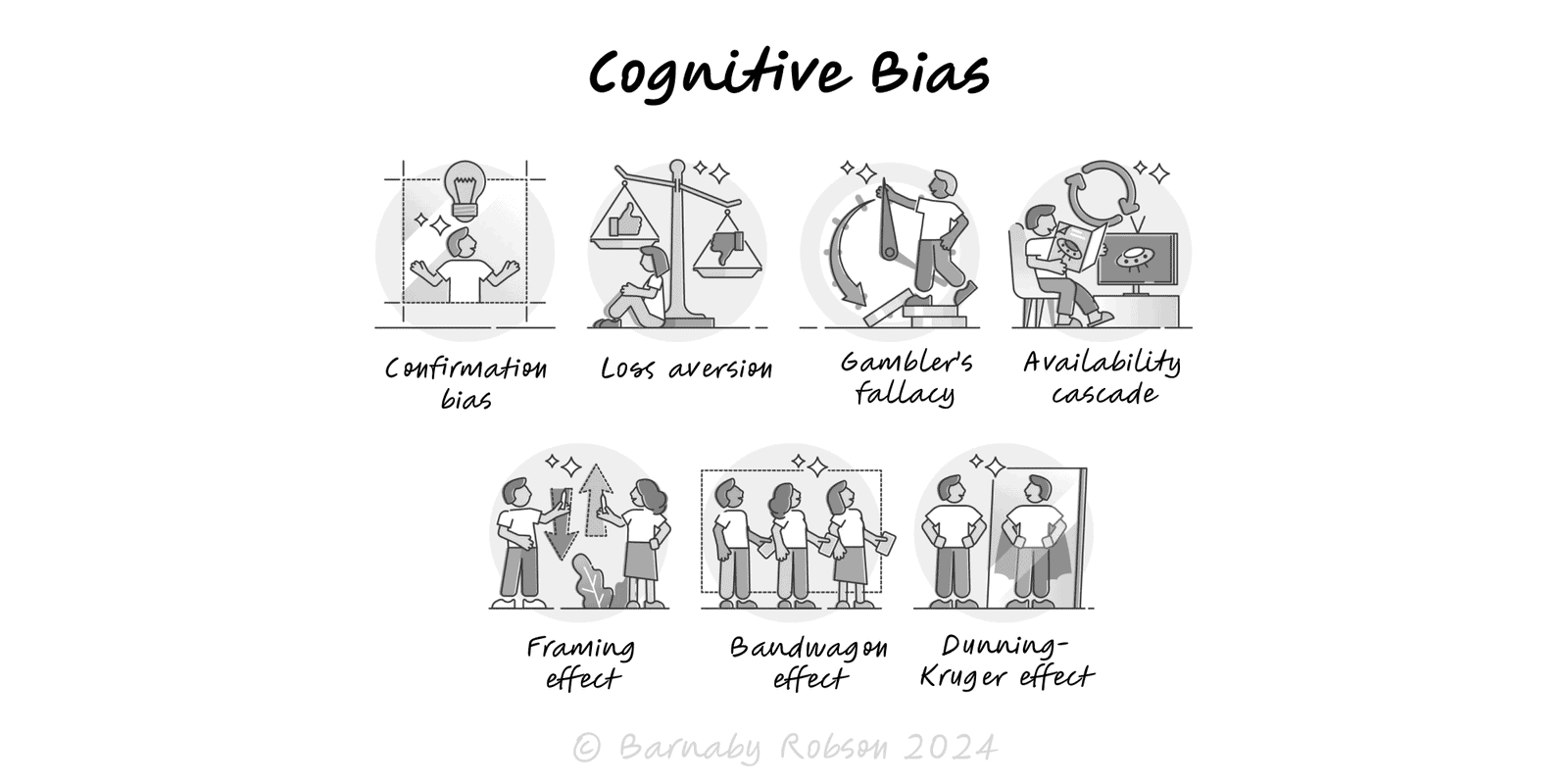

Cognitive Bias

Behavioural economics and cognitive psychology (notably Daniel Kahneman & Amos Tversky)

Cognitive biases arise because the brain uses heuristics to act fast under uncertainty. These shortcuts are efficient, but they tilt judgement in consistent ways—especially with noisy data, incentives, and time pressure. The goal isn’t to eliminate bias (impossible) but to shape processes so important decisions are less error-prone.

Speed vs accuracy – fast, intuitive processing (often “System 1”) trades rigour for speed; slow, analytical processing (“System 2”) corrects when engaged.

Common families (with examples)

Confirmation bias – we search for and overweight evidence that supports our prior.

Countermoves: pre-register disconfirming tests; assign a “red team”; force a “what would change our mind?” line.

Loss aversion – losses loom larger than equivalent gains (often ~2×).

Countermoves: show both frames (gain and loss); use long-horizon metrics; make reversible trials the default.

Gambler’s fallacy – believing independent events self-correct (“after five tails, heads is due”).

Countermoves: state independence/base rates explicitly; display binomial ranges; ban “due for” language in reviews.

Availability cascade – repeated, vivid claims feel truer and spread via social proof, regardless of evidence.

Countermoves: require source quality and independent confirmation; add a cool-off for viral topics; track what’s known vs said.

Framing effect – choices swing when the same facts are presented differently (e.g., 90% survival vs 10% mortality).

Countermoves: standardise wording; show both frames and absolute numbers with denominators; pre-set decision rules.

Bandwagon effects (herding) – people adopt beliefs or actions because others have, not because of private evidence.

Countermoves: collect independent estimates before discussion; use silent votes/Delphi; expose dissent and its evidence.

Dunning–Kruger effect – novices overestimate ability; experts may under-estimate variance and assume shared context.

Countermoves: calibration training (forecasting with feedback), checklists and peer review; compare to reference-class outcomes.

Context matters – stress, ambiguity, and incentives amplify bias; check the environment, not just the person.

Decision reviews for strategy, hiring, investment, pricing, and vendor selection.

Research & experiments – survey design, A/B test interpretation, sampling and power.

Risk & forecasting – reference-class baselines, ranges not points, premortems.

Communication – neutral wording, show both frames, order-effects control.

Ops & safety – checklists, standard work, second-checker on high-risk steps.

How to avoid

Define the decision & base rate – write the objective, options, criteria and a reference-class outcome.

Get independent estimates first – collect forecasts or scores before any discussion (prevents anchoring/herding).

Premortem – “It failed in 12 months—why?” Turn the top causes into mitigations or tests.

Consider the opposite – assign a red team and a “what would change our mind?” line.

Frame both ways – show gain/loss frames and absolute numbers with denominators; keep wording standard.

Check sampling – size, selection, survivorship, time window; prefer cohorts and hold-outs.

Pre-commit rules – thresholds, stop/scale criteria, decision windows; avoid ad-hoc pivots.

Run reversible tests – small trials beat argument; use expected value, not stories.

Calibrate – record probability ranges, track forecast accuracy, and retrain on misses.

Align incentives – metrics and pay should reward truth-seeking, not outcome theatre.

Bias-specific guardrails

- Confirmation bias: pre-register disconfirming tests; adversarial collaboration; ban HARKing.

- Loss aversion: use EV and break-even math; emphasise reversibility; evaluate over a longer horizon.

- Gambler’s fallacy: state independence/base rates; show binomial ranges or control charts.

- Availability cascade: require source quality and independent corroboration; add cool-off before big decisions.

- Framing effect: display both frames side-by-side; randomise presentation order.

- Bandwagon effects: silent votes/Delphi; capture minority reports and reasons.

- Dunning–Kruger: use checklists and supervision for novices; peer review; calibration training with feedback.

Checklist theatre – rituals without teeth; tie each step to a real go/no-go or redesign.

Bias labelling as argument – calling someone “biased” doesn’t resolve evidence; show the data and process defect.

Over-correction – slowing everything to a crawl; reserve heavy controls for material decisions.

One-and-done – biases reappear; keep a cadence of calibration and post-mortems.