Compound Interest

Jacob Bernoulli (roots in early calculus and finance)

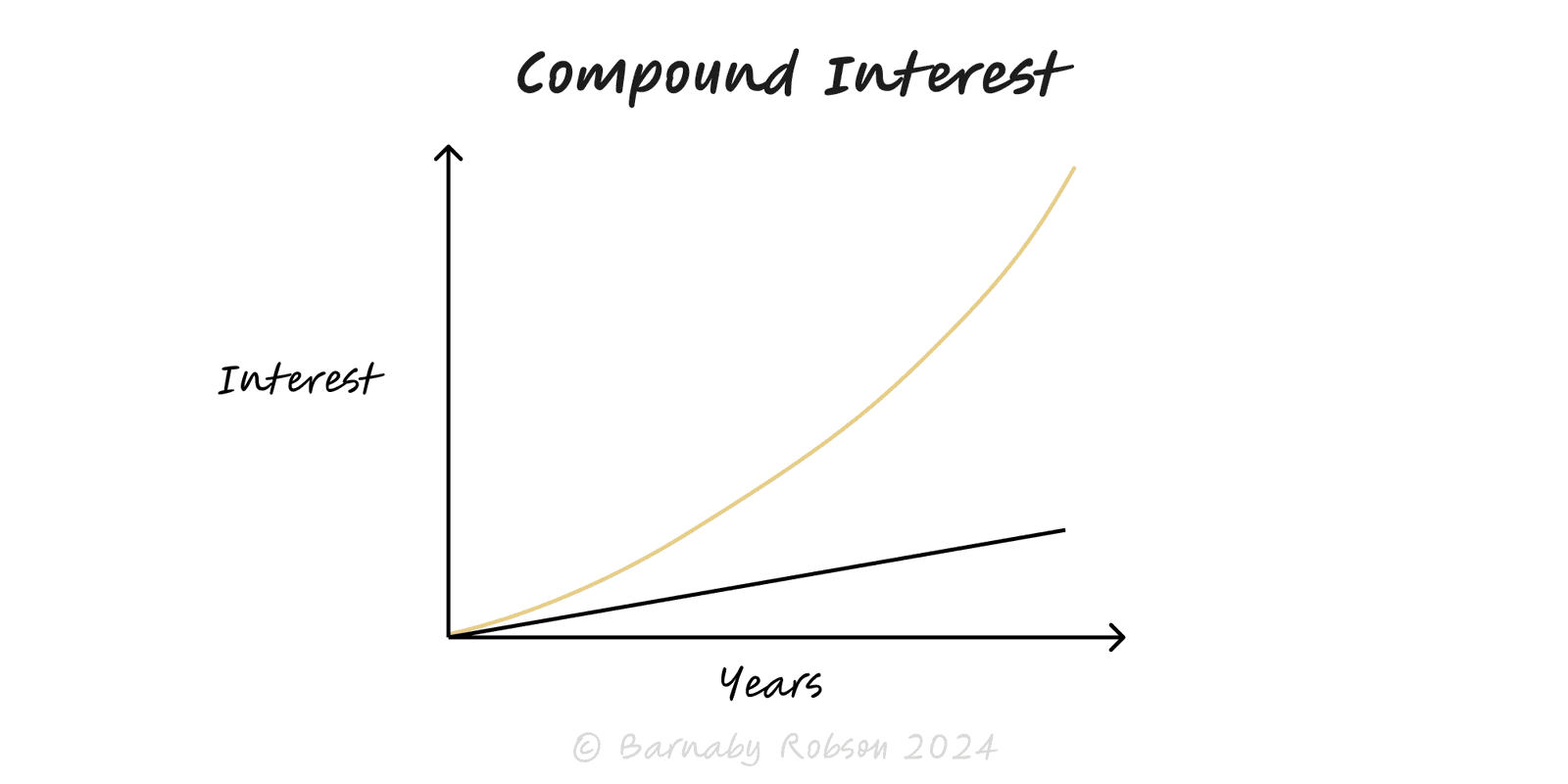

Compound interest is growth on both the original principal and the accumulated returns. With reinvestment, outcomes follow an exponential curve, so rate, time, contributions, and friction (fees, taxes, drawdowns) determine the end result. Used well, compounding is the most reliable engine of wealth and capability growth.

Core formula

- Future value: A = P(1 + r/n)^(n·t)

- P principal, r annual rate, n compounds per year, t years.

- Continuous compounding: A = P·e^(r·t).

- Effective annual rate: EAR = (1 + r/n)^n − 1.

Drivers

- Time – extra years matter more than extra contributions late on.

- Rate – small rate changes dominate long horizons.

- Frequency – more frequent compounding lifts EAR slightly.

- Contributions – steady additions increase the base that compounds.

- Friction – fees, taxes, inflation and drawdowns reduce the compounding base.

Rule of 72

- Doubling time ≈ 72 ÷ annual % rate (eg 72 ÷ 6 ≈ 12 years).

Investing and savings – pensions, ISAs, endowments, treasury ladders.

Business finance – retained earnings, reinvested cash flows, interest capitalisation.

SaaS and operations – customer retention and expansion compound revenue (NRR), learning curves compound productivity.

Debt – interest-on-interest works against you on credit balances and leveraged bets.

Set the plan – target capital, time horizon, and realistic after-fee return.

Automate contributions – monthly transfers remove timing excuses and average entry price.

Cut friction – minimise fees and tax drag; use wrappers and low-cost vehicles.

Protect the base – avoid large drawdowns; diversify and size risk so you stay invested.

Lengthen time in market – reduce unnecessary trading; let winners run where thesis holds.

Reinvest systematically – dividends, coupons and windfalls back into the plan.

Review annually – rebalance to risk, update assumptions, keep costs low.

Worked mini-examples

Savings: £10,000 at 7 percent for 10 years, annual compounding → £19,672.

Monthly investing: £500 per month at 6 percent for 15 years → roughly £146k contributed £90k.

Fee drag: 8 percent gross for 30 years at 1.5 percent fees vs 0.2 percent fees

8 − 1.5 = 6.5 percent net → ~6.6× P

8 − 0.2 = 7.8 percent net → ~9.1× P

Small fee differences compound to very large gaps.

Volatility drag – −50 percent then +50 percent ≠ break-even (you end down 25 percent). Focus on geometric returns.

Inflation – think in real terms; 7 percent nominal at 3 percent inflation is ~4 percent real.

Leverage and margin – magnify both gains and losses; guard against forced selling.

Sequence-of-returns risk – early bad years hurt more when withdrawing; adjust draw and risk near retirement.

Stopping reinvestment – spending income breaks the flywheel.

Chasing rate – reaching for yield can raise default risk and ruin compounding.