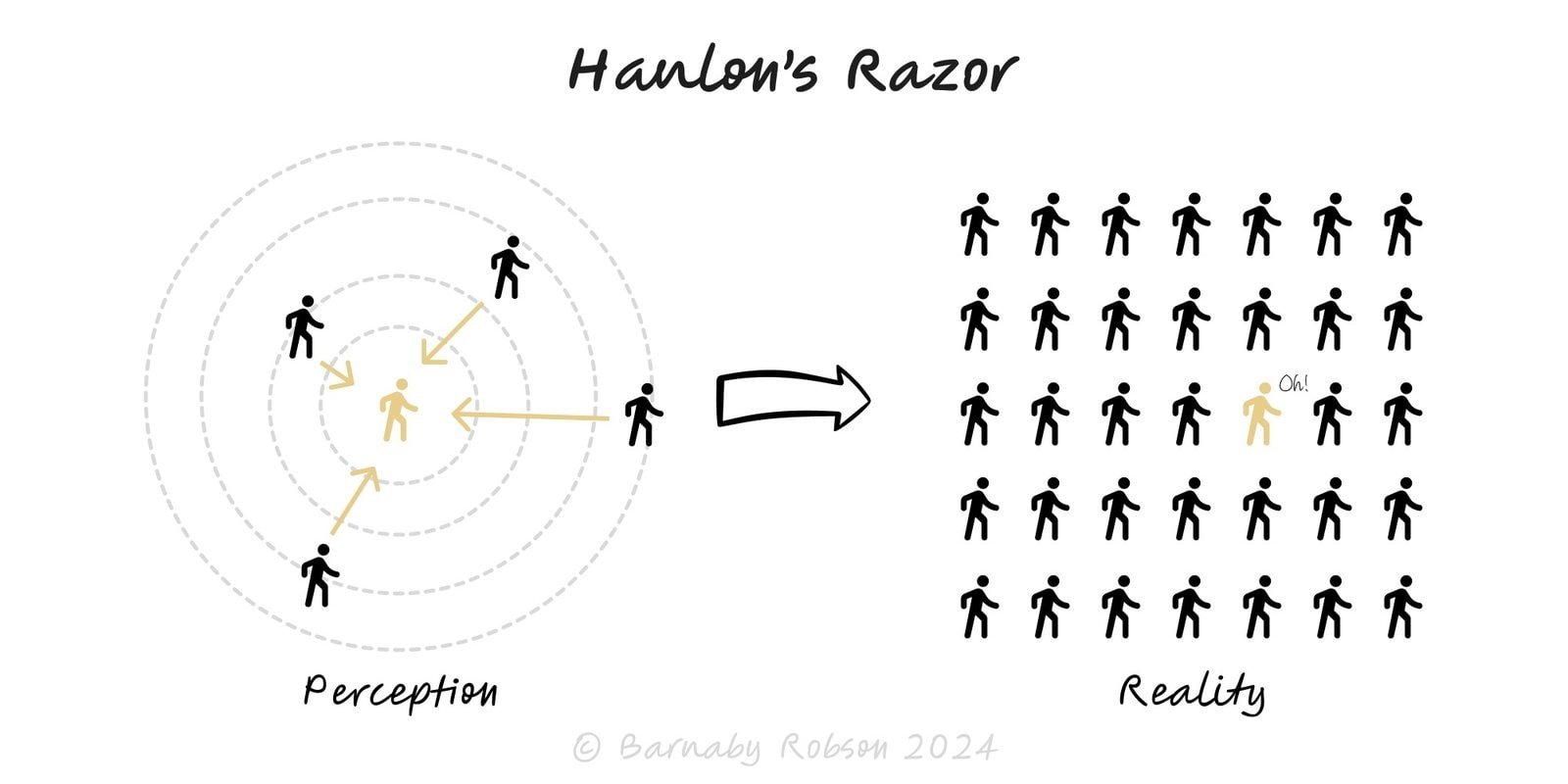

Hanlon’s Razor

Robert J. Hanlon (attributed, 1980); antecedents in earlier maxims

Hanlon’s Razor is a shortcut for interpreting setbacks and offensive outcomes. Most problems arise from mistakes, constraints or poor systems, not deliberate harm. Starting with a non-malicious explanation reduces conflict and speeds fixes—while leaving room to escalate if evidence of intent appears.

Base rates first – in most organisations, accidents and miscommunication are far more common than plots.

Causal stack – check systems and incentives before judging individuals.

Evidence threshold – require concrete signals of intent before concluding malice.

Reversibility – when stakes are low or reversible, assume error; when stakes are high, verify.

Incident reviews – outages, defects, compliance slips.

Cross-team friction – missed hand-offs, slow replies, conflicting priorities.

Customer comms – perceived “price gouging”, feature removals, policy changes.

Negotiation & vendor issues – delays or scope gaps more often reflect incentives or capacity.

State the harm neutrally – what happened, who was affected, and the observable facts.

Test the non-malicious hypotheses – error, ambiguity, capacity limits, misaligned goals, missing context.

Inspect systems – process, tooling, incentives, and interfaces that made the outcome likely.

Respond proportionately – fix the system first (clarify ownership, improve defaults, adjust incentives), then coach individuals.

Escalate on evidence – if patterns persist or you find clear intent, switch to accountability and safeguards.

Communicate with charity – ask for perspective, mirror back constraints, propose concrete next steps.

Naïveté – some contexts (fraud, security, adversarial markets) warrant assume risk, then verify.

Excusing everything – “no malice” ≠ “no responsibility”; keep consequences and learning actions.

Ignoring incentives – repeated “errors” under strong incentives are strategy by another name.

Cultural mismatch – blunt wording (“stupidity”) harms trust; use error/constraint language.

One-way door risks – for irreversible, safety-critical choices, require verification regardless of intent.